Author: Qualified mechanic John Cunningham. Published: 2021/07/06 at 9:20 am.

I carry a selection of just-in-case tools in the trunk because I’m a mechanic, and I feel separation anxiety when I’m away from my toolbox…. ah no. I carry them because crap happens, and I understand that feeling of helplessness when your car breaks down.

Having the tools and knowledge to help yourself and others is truly liberating. As a flat battery is one of the most common types of car faults, good jumpers and the knowledge to use them is important.

Cheap jumper cables are generally made from poor-grade materials. The cables are thin and shorter in length, and cable clamps offer a weak grip. Cheap jump cables offer resistance to the flow of energy between batteries. As a result, cheap jumpers are frustrating to use and offer inconsistent performance.

In this post, we’ll zoom in on the features to focus on when choosing a decent set of jumpers. We’ll cover how to safely and correctly jump-start your car, together with mechanics (me) and top jumpstarting tips. We’ll also cover some clever alternatives to regular jumper cables.

Features Of Quality Jump Cables

The truth is you might never use a set of jumpers. A set of jumpers are like a spare wheel, they’re useless until of course, you need them. It is you’ll agree better to be prepared, and in that mindset, what’s the point in buying a crap set of cables that may or may not work.

You’ll likely only buy one set of jumpers in your driving career; they don’t get a ton of use, so don’t wear out. It’s important to get this purchase right; you’ll be living with these jumpers for years.

I’ve been a mechanic for over twenty-five years, and as my father was a mechanic, too, I thought I’d likely been jump-starting cars for over thirty-five years. The jumper cables I’d buy are the 20 ft. 4 gauge Cartman booster available here on Amazon.com.

Here are the factors I consider when choosing a set of jumpers:

- Cable gauge

- Cable length

- Cable clamps

- Cable insulation

- Cable core type

Heavy Gauge Cable

When it comes to cable and the transfer of power, more is more. The cable is measured by gauge (GA). Gauge one being the largest, gauge two being smaller, and so forth. The gauge dictates the amps the cable can safely carry; gauge one, for example, may be rated at 800 amps.

A good set of jumpers should, therefore, be rated no lower than gauge four.

A larger gauge is important because it reduces the amount of resistance between the two batteries. It might be helpful to think of a jumper cable as a garden hose – a bigger hose allows for greater and easier flow.

A cable gauge of less than four tends to create resistance, and hot jumper cables are a common symptom. The heat is the power that should be helping power the dead battery, but since it can’t get there, it is instead converted to heat and is lost energy.

Higher gauge (smaller) cable may be fine for small-engine cars, but attempting to start a large car or truck will prove to be a pain in the ass.

Common problems associated with thin gauge jumper cables include:

- Inconsistent connection and hesitation on crank

- Excessive cable heat

- Melting cable insulation

Cable Length

Length is important; nobody plans to have a flat battery. If we did, we’d park on a hill or at least reverse into the drive. There are two solutions: push the vehicle to where it’s accessible or use a set of jumpers long enough to reach.

The second option is the smartest; that said, maybe you habitually reverse into the drive. If so, a ten-foot set of cables will suit you just fine. For most who drive regular-size cars/SUVs, we’ll need at least a sixteen-foot set. That allows the hero of the story to park behind the stranded vehicle and reach both batteries with comfort.

Longer vehicles will obviously require longer cables. If you drive a truck you may want to consider a twenty-five-foot set, pushing a truck isn’t fun.

Strong Clamps

Don’t overlook the importance of good clamps, not much point in having a solid gauge cable if the clamp is causing resistance. That’s correct; the cable clamp can be a source of high resistance, and it frequently is.

A good clamp must make a solid, tight connection to the battery in order to prevent resistance. Two types of clamp jaws are common. The wide opening Crocodile style clamp and the narrow Parrot style, both should offer side and top clamping. I prefer the crocodile style.

The very best clamps, like cable cores, are made from copper. However, the second-best option is the more common, embedded copper teeth.

Clamps should be sturdy, employ a strong spring, and be protected with insulation. The insulation is important as it prevents accidental shorting.

Cable Insulation

The cable insulation isn’t very exciting, I agree. But it might be worth noting the type of cable insulation on your new set of jumper cables. As batteries run flat more often in lower temperatures, you’re more likely to use your jumpers in lower temps.

Wrestling with cold, stiff, plastic-coated cables is so frustrating. The mind-bending puzzle of untangling them whilst crisis managing all the other crap that goes with a flat battery emergency is a form of torture.

Be kind to your future self, look for tangle-free flexible at low temp thermoplastic coated cables.

Cable Core Type

The metal type used in the core is a sign of the quality of the cables. Copper is a fantastic conductor of electricity; the very best cables are copper cores.

It is, however, more common for the core to be copper-covered aluminium. This is the second-best type of material.

How To Safely Jumpstart Your Vehicle

Jumpstarting your vehicle is quite safe once you follow the simple rules. Despite what many may say, there is no risk of electrical shock from jumpstarting. Regular gas and diesel vehicles run only 12-volt systems.

That is not true for Hybrid and EVs. There is a risk of electrical shock playing around with their electrical systems. The risk with jumpstarting comes not from electric shock but from the explosion and also the risk of electrical damage to car modules.

The explosion is rare but can happen. As you connect the final cable to complete the circuit when jumpstarting, arcing occurs (sparks). The problem is that a battery contains acid, and it vents acid vapours, which are flammable. Connecting the final jump cable, therefore, causes the aforementioned arcing, which could be a source of ignition. We will eliminate this risk altogether by grounding the final negative clamp away from the battery; it’s all covered below in the jumpstarting sequence.

The second risk involves connecting the cable’s backways, as in reverse polarity. In most cases, no damage occurs, but it is possible to blow fuses and damage some pretty spendy components.

Anyhow, we are not going to allow either of these to happen.

Pro Tips For Jump Starting

- Check both cars battery terminals are clean and tight

- After connecting the vehicles, run the engine of the donor car at 2000 rpm for a couple of minutes; it helps charge the flat battery a little before the actual jumpstart

- Keep the donor car running at 2000 rpm during the jumpstart process – boosts output

- Turn all flat battery consumers off, lights, radio etc.

- After starting the flat car, remove the jumpers and take it for a twenty-minute drive to charge battery

Connecting The Jumpers

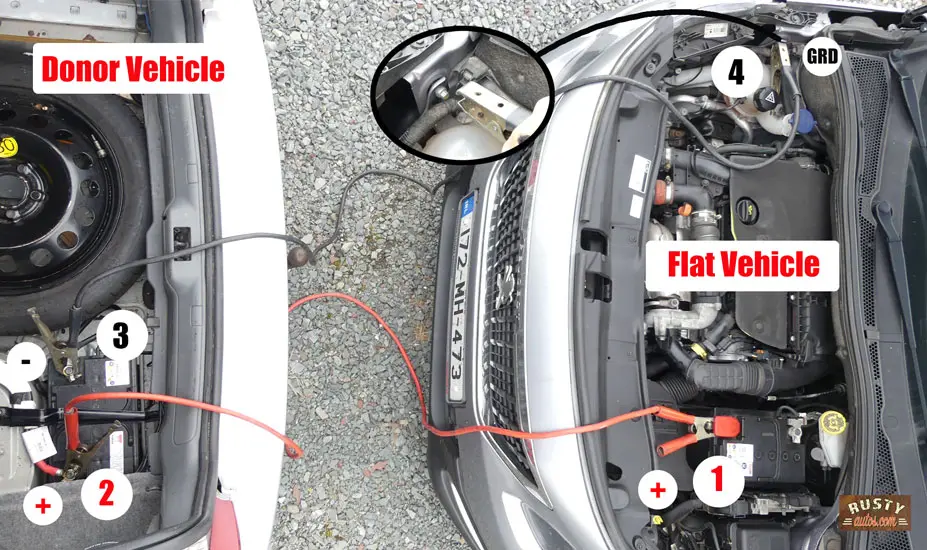

Follow the picture below. connect the battery cables in order 1, 2, 3, and 4. The final clamp (4) is grounded on the chassis or engine; this prevents the aforementioned arcing. A ground (GRD) is any bare metal on the chassis or engine.

After start, remove the cables in reverse order 4, 3, 2, and finally 1

Alternatives to Jump Cables

Now I understand if you don’t run the jumpstarting process every day, you may be a little rusty on the details. With that in mind, I’d consider the Smart jump cable set. It employs a warning indicator light to let you know if you are going wrong.

It also has a few other tricks, including a battery state of health and alternator test function. The jumpers are offered in 20 ft. length and in gauge four cable; you’ll find a link to them here on the “Trunk essentials page”.

If you don’t fancy hooking up another vehicle, or maybe you won’t have access to another power source, then consider the NOCO smart jump pack. Truly an amazing little tool. It has enough power to jump-start your car and yet is small enough to fit in the glove box (not that you should).

But that’s not all; it’s a real MacGyver of a tool. It contains a light, USB charge ports, it’s a battery charger, it won’t allow you to connect backways and has no arcing technology, I am a fan. You can check it out on the “Trunk essentials page” also.

What Causes A Flat Battery?

A flat or faulty battery is one of the most common problems a vehicle will suffer in its lifetime. The reasons for flat battery, however can vary.

Common among them include the following:

- Faulty battery

- Loose battery terminals

- Dirty battery terminals

- Faulty alternator

- Loose alternator drive belt

- Consumer left on, lights radio etc.

- Short in wiring

- Electrical component drain

- Accessories wired incorrectly

If you find your car battery keeps running flat, the first step towards diagnosis is to charge the battery. A flat battery can’t be tested. Jump starting the vehicle and driving the car for fifteen to twenty minutes or so with all consumers switched off is enough to bring the battery back to full capacity. Alternatively, use a battery charger; I’ve listed the charger I use here on the “Trunk Essentials page.

You can test your own battery using a DVOM or an inexpensive battery tester; check out this post, “Best battery tester for home use”.

You should note if the alternator is at fault, the battery won’t charge while driving and the engine will likely stall not long after disconnecting the booster cables.

If you suspect the battery and alternator are Ok, you instead suspect a short may be draining the battery then check out this post “Car fuse keeps blowing”.

A pretty common problem after a flat battery is an engine that suffers from an erratic idle, if that sounds like your problem check out this post “Car won’t idle after flat battery”.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

John Cunningham is an Automotive Technician and writer on Rustyautos.com. He’s been a mechanic for over twenty-five years and has worked for GM, Volvo, Volkswagen, Land Rover, and Jaguar dealerships.

John uses his know-how and experience to write fluff-free articles that help fellow gearheads with all aspects of vehicle ownership, including maintenance, repair, and troubleshooting.